Sensibility and Substance

Recent collages by Nicol Allan at Davis & Langdale

by Maureen Mullarkey

SENSIBILITY, A QUALITY DISTINCT FROM TALENT, is not easy to talk about. Talent is common enough; it shows up even in the darkest corners of Chelsea. But the distinguishing thing is sensibility, the ‘j’ne sais quoi that reigns over talent, exalting or misshaping it. Contemporary gallery culture cultivates a romantic mythology of the unique talent when what is truly rare is not talent at all but its informing spirit. Nicol Allan is an artist whose austere, understated works on paper achieve a rare delicacy that sets him apart from the minimalist ethos with which he can be superficially compared. Small, subdued compositions exhibit the contemplative taste of a Zen tea garden more than the studio-generated reductions of 1970s minimalism.

|

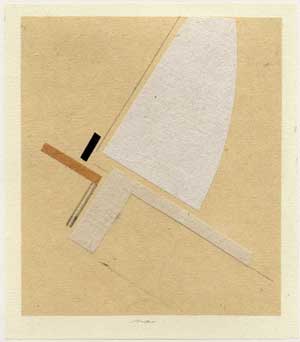

| Hölderlin-Zimmer #11 (2008) |

Born in Los Angeles in 1931 to Scottish immigrants, Allan is the grandson and great-grandson of stonemasons and small farmers in Aberdeenshire and Banffshire. Occupying Scotland’s stark, windswept northeast and touching the North Sea, both regions are rich in Neolithic and Bronze Age archeological sites. Something of the archaic quietude of his ancestral homeland pervades his collages.

Recent pieces are constructed largely of handmade English and European papers and Japanese tissues. A few spare elements—died, stained or natural-toned rectangles or segments of a curve—are cut and composed with lapidary precision. A straight edge is notched just so; the interstices between two paper shapes diminish in tandem; the discipline of a ruled pencil line is balanced—or, more accurately, contradicted in space—by the echo of a freehand mark. Each construction invites wakeful attention. These solitary and tranquil works were not made in a hurry; neither can they be taken in at a quick glance.

“Hölderlin-Zimmer #11” (2008) is a jewel of oppositional forces made with only three pieces of paper and two slight pencil notations. A slender, dark ochre column runs vertically down the center of a paper the color of wheat. A dense black shaft at the base recedes into space, suggesting a shadow and, simultaneously, lending an illusion of solidity to the rectangle. But that suggestion is undone by a convex pencil line that issues from the opposite side of the same base. Atop the central form, but not quite resting on it, hangs a mottled, jagged device with a downward thrust like overhanging eaves. Its angles are exquisitely indented to skim corresponding cuts in the upper edge of the column. As in all of Allan’s work, spacing and exactitude are everything.

Of the 20 collages on view, several dated back to the 1970s and 80s.. These are works from earlier series based on motifs from nature: a mountain, a wave. The rest, all executed between 2008 and 2009, include three homages to Albert Pinkham Ryder plus seven seried under the title “Hölderlin-Zimmer.” Both tags are intended to evoke whispers of oddity that can only be thought biographical.

Friedrich Hölderlin (d.1843), little understood in his lifetime, gained a posthumous reputation as a high point in German lyric poetry. Declared insane shortly before he died, Hölderlin spent most of his adult life in the care of kindly, cultivated Ernest Zimmer and his family. Allan’s titular reference invites the scholarly game of finding analogies of some kind. It also satisfies the dark strain in American romanticism that likes its artists, if not tortured, at least peculiar. That hint of peculiarity is reinforced by homages to Ryder who retreated into seclusion as he aged.

|

| Composition VL, 1981-84 |

Little is known about Allan who seems to prefer it that way. He has never been to the gallery; neither Roy Davis nor Cecily Langdale have ever met him. All transactions have been conducted either by letter or through Allan’s wife. On the one hand, it is a relief to be spared the distraction of biographical details that too frequently color reception of an artist’s work. On the other, one is left wondering whether Allan’s chosen titles signal a self-conscious theatricality.

But contra the Romantics, Allan’s work has no darkness in it. Quite the opposite. It is marked by what the medieval Scholastics called claritas. More than simple clarity — though that, too — the word, in its Latin inflection, indicates a brilliance not reducible to any particular content. It points to a conception of beauty that points toward the sublime. A tiny, monotonal collage like “Composition VL” (1981-84), its pale paper shards punctuated by a sliver of dense sumi black, reminds the viewer that light itself is a material substance.

Reference to Ryder carries conviction on a deeper level than that of eccentricity. Like Ryder, Allan was largely self taught as a painter and draughtsman. Like the older man’s art, his is the product of an intense inner experience, little influenced by trends around him. His seclusion — if that is the word for it — is imaginative. In that gracious separation between Allan’s sensibility and shifting fashion lies a promise of timelessness.

Davis & Langdale Company, Inc. (231 East 60th Street, NY 10022, 212-752-7764) from April 4 to May 2, 2009.

Copyright 2009 Maureen Mullarkey