Out to Lunch, Again

Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” in perpetuity at the Brooklyn Museum

By Maureen Mullarkey

It is only a matter of time before museums begin burying mogul benefactors on site, like kings at Westminster. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn Museum’s new Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art makes do as a crypt for “The Dinner Party,” Judy Chicago’s moribund monument to the gullibilities of identity politics. Obsequies begin tomorrow in the world’s first cathedralette to feminism as a category of art.

Built by a transient pool of female volunteers who traveled to Ms. Chicago’s West Coast workshop at their own expense, “The Dinner Party” opened in San Francisco in 1979. It was first exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum a year later. A best-seller, the project went on the road and then into storage for two decades. Thanks to the tenacity of Through the Flower, the non-profit foundation Ms. Chicago established to promote it, the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation bought the relic and enshrined it, Lenin-like, on the museum’s renovated fourth floor. (Ms. Sackler is a trustee of the museum on whose behalf she accepted her own gift in 2002.)

|

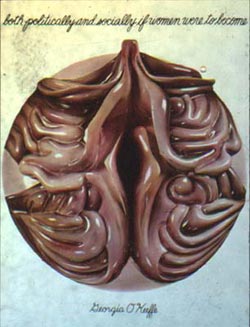

| Judy Chicago,The Dinner Party, Georgia O'Keefe |

Press material trumpets the work’s “dazzling new quarters” but avoids its specific content. A huge triangular table is laid with 39 place settings representing the stylized pudenda of specific women, real or imaginary. Vaguely suggestive of an open flower, each serving-platter-sized vulva is prettily decorated with emblems of the woman’s attributes. This is Ms. Chicago’s “butterfly-vagina” imagery, a box lunch for women hungry for affirmative symbols.

Liturgical trappings and inspirational tags are everywhere. Dinner guests include Ishtar (“Great Goddess of Mesopotamia, the female as giver and taker of life, whose power was infinite”) and Amazon, representing “Warrior Women who fought to preserve gynocentric societies.” About the grounds for such societies, Margaret Mead wrote: “All the claims so glibly made for societies ruled by women are nonsense.” But mistaking goddess worship for evidence of women’s primordial status is fundamental to guerrilla anthropology. And it coincides with the neopagan revivalism that has been a secular refuge from Enlightenment rationality since the nineteenth century.

Feminists find nothing askew in depicting the variety of women’s achievement in terms of labial display. Emily Dickinson’s mortal privacy and the granite of her inventiveness are honored by a flirtatious, pink lace crotch resembling a Victorian tea cake. Virginia Woolf, who repeatedly rejected emphasis on the sex of a writer as superfluous, is just another floral orifice. Composer Ethel Smyth’s vaginal opening is formed by the curve of — guess! — a baby grand. On it goes, down the length of this cunnilingus-as-communion table.

The incongruity of the imagery and its sober feminist purpose is lost on susceptible women. The installation’s vulgarity is inseparable from its inane solemnity. “The Dinner Party” exploits its era’s zealous insistence on women’s supposed intimacy with nature, a solipsism that ultimately affirms the old canard that the center of a woman’s creativity is between her legs. The work’s reductive silliness is entertaining; its mendacity is not.

Christina Hoff-Sommers’s distinction between equity feminism and gender feminism is useful here. The first is a mainstream movement that sought for women the same rights as men (historically hard won for common males). The latter is a militantly partisan, academic kriegspiel that applies the boilerplate rhetoric of class struggle to relations between the sexes. The feminist art movement stems from gender feminism.

It was spurred by Linda Nochlin’s famous 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” The answer is that the movement did not really want any. It preferred sneering at “the myth of the Great Artist” and indicting the nature of art. Professor Nochlin complained that no appropriate “language of form” existed for women. In short, women could not be judged by “male” standards of quality. These were “intellectual distortions,” pretexts for the “unstated domination of white male subjectivity.”

Protectionist and retrograde, the argument was a goddessend for a trick of the bazaar seeking strength of numbers. False opposition between women’s abilities and concepts of excellence opened the floodgates to self-assertive levels of amateurism. These now carry the imprimatur of a once eminent museum.

The feminist art movement rallied those women whose resentments welcomed an assault on taste. Ideology gilded mediocrity — and ritual grousing — as celebrations of “women’s way of knowing.” Consequently, women’s magnified presence in the arts (rather than, say, statistical mechanics or electro-optics) is a cheap grace. Any segregated body devoted to women’s “different voice” in art valorizes the unremarkable.

Tailpiece to the women’s studies industry, the Sackler Center and its programs are undoubtedly expected to pump attendance. Box office concerns have led the museum down the primrose path before. (Conflicts of interest surrounding its 1999 exhibit “Sensation” are widely documented; and the Better Business Bureau’s current Charity Report finds the museum lacking in certain standards of accountability.) This time, financial considerations joined crackpot philanthropy to institutionalize a faded movement’s opportunism and anti-intellectualism.

A candid stocktaking of that movement and of Nochlin’s role in it would be useful. The Sackler Center makes any such appraisal unlikely. Ms. Nochlin herself co-organized one of its inaugural exhibitions, “Global Feminisms.” And the accompanying ceremonial exhibit “Pharaohs, Queens and Goddesses,” is only the first in a series showcasing themes from “The Dinner Party.”

Exaggerated grievances and fantasied matriarchal utopias were titillating for a privileged generation of Western women free to play at trouncing the male gaze. But that was in another century. Now, the jihadist gaze surveys us all. Expect the ideologically driven Sackler Center, with the 1970s on perpetual wake, to blink and look away.

Lost in the ballyhoo over women and art is recognition that the sole, significant cultural artifact of the feminist movement was never an artwork. Its true consummation — perfect testament to Ishtar — was the vacuumed womb. Around the catafalque at the Sackler Center, vacuumed wits pay their respects.

A variation of this review appeared in The New York Sun, March 22, 2007.

Copyright 2007, Maureen Mullarkey