A Feast of Malfeasance

“Fakes and Forgeries: The Art of Deception” at Bruce Museum

By Maureen Mullarkey

FAKING IT IS AS OLD AS THE RECORDED HISTORY OF ART. The fifth-century B.C.E. sculptor Phidias is said to have signed the work of talented students. Young Michelangelo purportedly added a false patina to a statue sold to Cardinal Riario, astute collector of antiquities, as a genuine antique.

Fast forward to 1999 when 28 Georgia O’Keefe watercolors were removed from the canon. The suite had previously sold for $5 million after reported endorsement by the O’Keefe Foundation and the National Gallery of Art. In 2000, Sotheby’s and Christie’s were embarrassed to learn they each held the one and only “Vase de Fleurs” by Gauguin. And consider those legions of small, unsigned works still beckoning scholars whose enthusiasm outweighs their discernment. The sheer scale of falsity prompted Newsweek’s celebrated quip that of the 2,500 paintings Corot made in his lifetime, 7,800 were in the U.S.

The Bruce Museum’s “Fakes and Forgeries: The Art of Deception” surveys the history of deceit in Western art with uncommon candor and lively scholarship. It is a rousing tour through intrigue, misattributions, copying and creative acts of identity theft. It covers sleights of hand from forged documents and false provenance to technical procedures used to fabricate historical works.

|

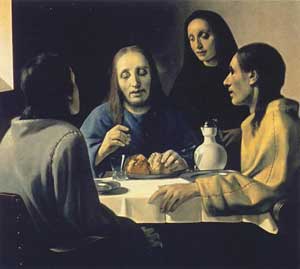

| Han van Meegeren, Christ and His Disciples at Emmaus, 1936-37 |

Treating sculpture, manuscripts, Gothic ivories, decorative arts, painting, prints and photographs, this feast of malfeasance holds as much for scholars and collectors as for the general public. The show is authoritative, instructive — and wicked fun. The earliest forged styles on view are Egyptian, Greek and Assyrian, from which the show moves chronologically through historical periods to the modern era. The caliber and scope of counterfeits exhibited, most from prestigious collections (as well as from the FBI), is startling.

From Piero to Pollock, brand names of every period are widely faked. But the forgery market also keeps pace with contemporary trends. Forgers are driven, like collectors themselves, by high auction prices. Forgery extends even to artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat who are not traditional blue chips.

Han van Meegeren’s “Christ and His Disciples at Emmaus” (c.1936), painted in the style of Vermeer, is likely the most renowned forgery in the world. It is thrilling to have it here. Vermeer’s output was so small that this “hitherto unknown painting,” created a sensation when its discovery was announced in 1937 by art historian Abraham Bredius. Van Meegeren’s saga, his disdain for the art market and his post-war trial for collaboration (selling a “Vermeer” to Hermann Göring) is a modern legend. His canon of forgeries — the works Vermeer should have painted — is not yet settled. Suddenly, Cynthia Ozick’s phrase “the implausibility of originality” takes on real meaning.

A quasi folk hero among forgers, Eric Hebborn (1934-96), sometime protégé of scholar and spy Anthony Blunt, is represented by a faux Mantegna drawing owned by the Morgan Library. He inscribed “Andrea Mantegna” on the sheet and manufactured a provenance that included ownership by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

A convincing still life in the manner of Édouard Manet was exhibited in the 1913 Armory Show as an example of his contribution to the development of modern art. A deft “Giacometti” painting of a seated nude is by the versatile John Myatt (b. 1945) who gave up illegal forgery for the legitimate kind. Although he still signs each forgery on the front with the artist’s signature, the back is now inscribed “Genuine Fake.”

What van Meegeran was to Dutch Masters, Brígido Lara (b. 1940) is to pre-Columbian pottery, of which he claims to have created 40,000 pieces. He continues to sculpt in ancient styles but, chastened by arrest in 1974 for trafficking in antiquities, now signs his work.

The Rospigliosi Cup from the Benjamin Altman collection, once attributed to Benevenuto Cellini, has been proven either a 19th century copy or an outright fraud. Nevertheless, the Met still exhibits it, discreetly labeled, on grounds that it is beautiful.

Museums are reluctant to concede errors or embarrass donors. When large investments and reputations are on the line, open admission that someone has been misled risks suit for libel or product disparagement. Besides, if a museum is courting a certain collector to donate his Cezanne, should it bypass his dubious Cassatt being pressed on it for an upcoming exhibition?

More people are responsive to signatures — trademarks — and the cachet of possession than to art itself. Forgeries, then, will be with us forever. That is why this comprehensive, imaginative exhibition is compulsory for anyone who would understand the cultural politics and gamesmanship of authentication.

The issues involved have profound implications that go beyond the monetary stakes to the credibility of experts and matters of public trust. Bruce director Peter Sutton summarizes the show’s purpose: “ [It] challenges museumgoers to ask fundamental questions about what constitutes authenticity and originality in a cynical and occasionally mendacious art world.” Both the exhibition and its detailed catalog serve warning to the inexperienced and the credulous and invite extended discussion.

A scholar in his own right, Mr. Sutton contributed a major essay on connoisseurship to Robert Spencer’s “Fakes and Forgeries” (2004), a book which cautioned that “truth in labeling does not always pertain to what changes hands in the present day art world.”

(A variation of that essay appears in the catalog.) Senior curator Nancy Hall-Duncan is frank: “In the late twentieth century, forgery, like art itself, became big business.… [and] the temptation to misrepresent art has become stronger and more lucrative.”

Thoughtful viewers will come away more attentive to conflicts of interest among appraisers. The Art Dealers Association of America, for example, maintains a prominent appraisal service, contending that dealers are best equipped to establish value precisely because they make their living from the market. Viewers may have their own thoughts on whether this is a species of poacher-turned-gamekeeper.

With art the new bullion, the

culture can not afford to have its currency debased. Hats off to the Bruce for a confident tutorial on why fakes matter.

“Fakes and Forgeries: The Art of Deception” at Bruce Museum (One Museum Drive, Greenwich, Ct., 203-869-6786).

This essay first appeared in The New York Sun, May 10, 2007.

Copyright 2007, Maureen Mullarkey