A Radical Postal Clerk

Arnold Friedman at Hollis Taggart Galleries; Bruce Gagnier at Lori Bookstein Fine Art; Ed Musante at Paul Thiebaud Gallery

By Maureen Mullarkey

RECOGNITION COMES SLOWLY TO MODEST MEN. It eluded Arnold Friedman (1874-1946) in his life time. His painting has only recently begun to gain the acknowledgment it deserved. This full-scale retrospective, the first of its kind since the Jewish Museum’s 1950 memorial exhibition, is an exhilarating step toward redressing the oversight.

|

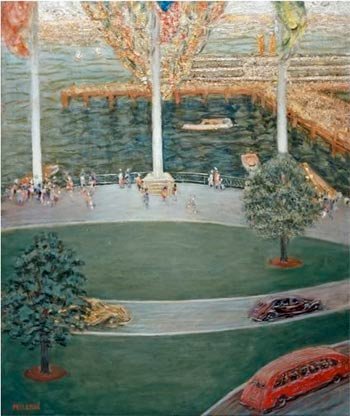

| Arnold Friedman,The Basin, 1938 |

Clement Greenberg declared him “one of the best painters this country has ever produced” and “the only original landscapist left in this country after Marin.”

The man who made Jackson Pollock a household word, Greenberg praised Friedman but patronized him at the same time. In 1945, he commented: “Friedman had trouble finding himself—he earned his living as a post office clerk.” Two years later, in the artist’s obituary, he restated the deprecation: “Friedman was forced to make his living as a post office clerk and to paint in his spare time.”

Friedman saw it differently. As he scrawled on the verso of a 1943 still life: “The Post Office? Yes, the Post Office. It was tough, very tough but it yielded a measure of independence and responcible [sic] citizenship. What American painter was permitted to retain them? Speak up!” Pollock’s puerile recklessness in the Hamptons ultimately cost him more time than Friedman spent in the post office. But cultural myths, like primitive gods, feed on blood sacrifice—not family life in Queens.

Art historian William Agee curated this show of nearly 50 paintings, all but 15 borrowed from private collections. His choices are insightful and wide-ranging, beginning with the Seurat-like “Artist at His Easel” (1908), passing to Synchromist abstractions from 1918-19, the classical monumentality of the 1920s and the simplified geometric forms—tagged Purism—promoted by Le Corbusier. Friedman’s variety of approaches illustrate an easy familiarity with art history and the aesthetic directions of his own time. But his most enduring affinity was with Bonnard, evident in the interior “Still Life with Barcha” (1943).

The constant beauty of Friedman’s paint unifies his experimentation and multiple subjects. In the resplendent “Skier, Island Pond Vermont” (1938-39), variegated whites spread across the panel like clotted cream. The sky and the skier’s torso are buttered in. Everything else—the man’s legs, the flanking trees, reflections of a brilliant sky on snow—emerge from delicate washes drawn, shimmering, on the surface. Many later paintings play luminous passages of smooth emulsion against areas of encrusted color. In “Shore Path” (1940), the curving bicycle path is fluid and level, but the adjoining stretch of sand is granular, paint texture miming the reality of the subject.

The truly stunning revelation of this show is the radical character of Friedman’s late work. "Spider in the Web" (1943) anticipates an equally small (8 by 10 inches), splendid untitled work from 1944. Here is the totally abstract, unaccented, all-over method Pollock is credited with originating. Intricate weavings of paint are almost preternatural. How did Friedman work these multi-hued threads of paint into a dimensional whole without flattening or muddying understrokes?

To what extent did Pollock owe his all-over style to Friedman’s innovations? Only Greenberg knows and he is not here to tell us. Nevertheless, after you have seen Friedman’s abstractions made in the early 1940s, several years before Pollock began his drip paintings, you recognize the older man as the seminal innovator.

IN THE WAKE OF WORLD WAR II, Jean Mouroux wrote: “What is at stake in our civilization is whether man shall remain—or re-become—a sacred thing.” The meaning of man is no clearer now than it was six decades ago; Mouroux’s hoped-for restoration of man to his dignity seems more elusive than ever. Bruce Gagnier’s sculpture incarnates the French scholar’s assertion of the mystery and tragedy of bodily existence.

|

| Bruce Gagnier, Greenpoint, 2004 |

These anxious and misshapen nudes are strangely moving, beautifully crafted testaments to the misery of the body. Mr. Gagnier calls his figures self-portraits but they admit a more universal truth: that the sting of the flesh does not reside in mortality alone. It lies, too, in the myriad ways the flesh that describes us betrays the spirit that defines us.

Half-life size, each figure is created in hydrocal, a gypsum product stronger than traditional plaster but similar in workability. An ancient and versatile medium, plaster can be combed and indented like clay, filed and carved like wood. Mr. Gagnier makes inventive use of every available technique to wound his figures in denial of carnal hopes. Eyes are sewn shut with small strips of cloth soaked in the medium. These “bandages” are added incrementally for texture and bulk throughout the figures. Patination, an expressive component in its own right, emphasizes the irregularities of pitted surfaces and, with them, the temporality of the subject.

“Greenpoint” (2004) is particularly compelling. Its grotesqueries are refined by fidelity to anatomical facts, distended but still convincing. A thickened female stands undone by time and gravity at work on human clay. Arms hang low, a hint of primate ancestry that mocks the nobility of classical canons of perfection. Feet cling to the ground with a sturdy simian grip, defying the promise of dissolution that cries from the unruly form.

Four paintings are included in the show. Elegant exercises, they lack the confessional power and humane resonance of the sculpture. They would be better exhibited separately.

BIRDERS AND LOVERS OF FINE PAINT HANDLING will devour Ed Musante’s first New York solo show. So will anyone susceptible to the graphic splendor of vintage cigar boxes.

Mr. Musante is a Bay Area artist who paints a single bird on the lid or bottom exterior of old cigar boxes. The artist’s attraction to birds themselves came after he began painting them. The initial spur was not nature but Nathan Oliveira’s hawk series. Now the painter is an avid birdwatcher, smitten with the particularities of each species.

|

| Ed Musante, Blue Jay / Punch, 2006 |

The boxes are intact, unstripped of original labels and decorative edgings. Their ornamental trim contemporizes each avian portrait, depicted with traditional means and lively sympathy. Color correspondences between plumage and the box’s original embellishments bind the various species to their supports.

Mr. Musante works with dry pigment suspended in acrylic gels, a technique that provides both translucency and the viscous beauty of oil paint. Wood grain enhances the downy texture of bird bodies or, carefully left bare—as in “Peregrine / John Reading” (2006)— turns into a rock or twig for landings. Embossings and stampings show through the paint, creating delicate collage effects. This heightens surface interest, preserves the character of the box and creates opportunity for visual puns that lend whimsy to the expressive immediacy of the paintings.

An imperious hawk stands at attention on a blackened Arturo Fuente box, just the pose for a regal hand-rolled cigar. A small Summer Tanager flits onto a slim box of Fonseca Cadettes, a quick smoke. A goldfinch, emblazoned with dark wings and white wingbars, grips a branch wittily formed from a length of exposed boxtop. Heading the composition is the cigar maker’s motto “Made Good.” And it is.

Artminds will grouse that Mr. Musante’s work is askance of the strategies of contemporary painting. It fits no recognizable schema, represents no movement, and—most grievous—requires no intercession from the critical brotherhood. Quite so. That is its great charm. Good birding, everyone!

“Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint” at Hollis Taggart Galleries (958 Madison Avenue, 212-628-4000).

“Bruce Gagnier: Sculpture” at Lori Bookstein Fine Art (37 West 57th Street, 212-750-0949).

“Ed Musante: Cigar Box Paintings” at Paul Thiebaud Gallery (42 East 76th Street, 212-737-9759).

This review appeared first in The New York Sun, June 1, 2006.

Copyright 2006, Maureen Mullarkey