From CityArts

Irving Petlin’s paintings; Bernardo Siciliano’s girlie pix; a Leonardo da Vinci for Times Square

by Maureen Mullarkey

POLITICAL GRANDSTANDING IN THE ARTS IS NOTHING NEW. Art tethered to the purposes of social policy or political postures is solidly entrenched in contemporary culture. Much of today's art mimics the intellectual fray of the 1960s, itself an imitation of contests begun in the 1910s and '20s.

It is against this backdrop that Irving Petlin (b. 1934) has acquired near-iconic status. In the

Sixties, he embraced the assertion of Leonid Ilychev,

Kruschev's spokesman for the arts,

that “Art belongs to the sphere of ideology.” In the decades since, he

has combined art and activism, ending with poster designs for Barack Obama and

one-dimensional disavowal of “the murderous israeli

siege of Gaza.” Along the way, he cemented friendships with Leon Golub (d. 2004) and R.B. Kitaj

(d. 2007). Their triumvirate established what is still the template for

socially engaged—defined as left leaning—painting.

Happily, Petlin is

a more subtle artist than he is an ideologue. With

pieces dating back to 1977, this exhibition is a fine introduction to his

oeuvre for new audiences and a welcome revisit for others. There is no denying

the seductiveness of the work on view. The tug of politics resides mainly in

loaded titles. Petlin's gift, on canvas, was for the

enigmas of representation. Absent the titles (e. g. Hebron, 1999; Gaza/Guernica, 2009),

the paintings remain illusive, elegiac traces of the sorrow implicit in every

historical moment

Petlin paints—possibly in spite of himself—not events at all

but rather the emotive residue of them. Here is the condition of man who

suffers his times, haunted by danger and melancholy. The pastel, Trestle Bridge/The Next Village (1990), is a compelling illustration of the

way Petlin transmutes mimesis into suggestion,

facilitated by a trembling, near-pointillist touch. As your eye moves across the bridge the supporting girders

gradually take on the shape of bones, emphasizing the spectral quality of the

semi-abstract figure huddled in one corner. A village burns in the distance.

The where and why of it are left to the viewers projections. Mood is the single

reality: a poetic evocation of mortal evanescence, loss and pain.

Irving Petlin at

Kent Gallery, 541 W. 25 Street, 212-627-3680.

•

• • •

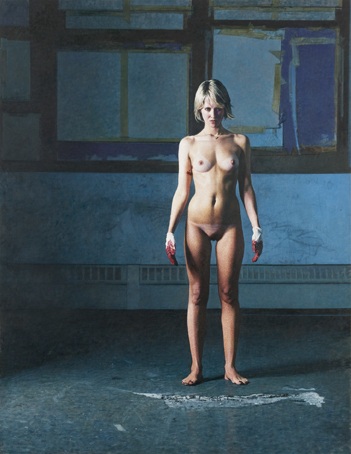

HAS SUCCESS SPOILED BERNARDO SICILIANO? Admirers of his assertive, elegantly designed cityscapes must

wonder.

Son of celebrated Italian writer Enzo Siciliano, Bernardo arrived

preselected for mythic status. His 1976 debut in Rome was introduced

by poet and critic Attilio Bertolucci.

He was just seventeen, cosseted by all the right literary, cinematic, and

theatrical circles. Before he was thirty, he was being packaged as a legend

with a bio stocked with ingredients similar to those of the young Balthus, from family connections to the designing of high-profile

opera sets. Now forty and a New Yorker, Siciliano

looks less like a prodigy than a talent coarsened by premature celebrity.

Parallels with Balthus

hover like Poe's raven over this current show at Forum. A characteristic architectural composition, Chinatown (2009), provides counterpoint

to five monumental female nudes. It is hard to reconcile the sensibility at

work in the single urban view with the 90-inch- high girlie pix that trick out

the display. The roofscape's compelling geometric

complexity and cool tonalities have nothing in common with the figures except

an underlying dependence on the camera.

It has been done before, this oversized

naked format. William Beckman, an older Forum durable, was the doyen, for two

decades, of 8-foot figures in the buff. But he never smirked. You greeted his

confessional nudes with the surprise you might feel if you opened your

neighbors' door without knocking and caught them undressed. By contrast, Siciliano's gals have been waiting for you, artfully posed

until you get there. All have that paid-by-the-hour grimace of bored extras in

a skin flick. Jackie and Nicole leave their boots on, just in case. Janelle

spreads her legs for a centerfold crotch shot.

Ms. Bloody

Gloves (2009) shaves her pubis and sports an ambiguous mark on her right

side. A burlesque of the ecce

homo motif or just a blond finger-painting in the raw? What matters

here is the collapse of true ability into photographic mimicry and full frontal

banality. Compare Balthus' echo of an ecce homo in The Room (1952) and no more words are needed.

Through March 13. Forum Gallery, 745 Fifth

Ave., 212-355-4545.

Both essays above appeared first in CityArts, January 26, 2010.

• • • •

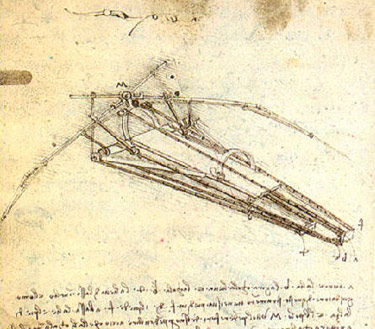

LEONARDO DA VINCI’S WORKSHOP IS AN

INGRATIATING TOUR DE FORCE that succeeds as spectacle, if lite as history. From the introductory film, through the

digital recreations of The Last Supper and Mona Lisa, to the interactive displays

and wooden models of Leonardo’s sundry engineering designs, the exhibition has

all the ingredients for an absorbing family outing. There are Disneyesque touches to captivate any youngster: that

marvelous skeleton, a mechanical lion, leather bound quartos in period stage

sets, a life-sized robotic soldier, war machines—the whole panoply of

detailed simulations of Leonardo’s technological musings.

Historians consider it unlikely that any of

the schemes sketched in the Codex Atlanticus, Leonardo’s encyclopedic collection of notes

and drawings, were ever realized. Exhibition blurbs admit that the artist’s

designs are incomplete and the notes difficult to decipher. Yet whether these

plans existed off the page is beside the point. The models aim to demonstrate

that they “could have” worked if constructed in particular ways. More

significantly, they make concrete the character and breadth of Leonardo’s

prodigious curiosity. In that sense, the models are exhilarating, even

instructive in unintended ways. They suggest that our inner

lives—certainly our children’s—would be richer if we stopped

texting and carried a notebook instead.

The project is the brainchild of Leonardo3,

an entrepreneurial venture that blends scholarship with showmanship to

popularize knowledge of Leonardo. Think P.T. Barnum for the digital age.

Apotheosizing da Vinci as “the greatest genius that

ever lived” is infotainment hyperbole that plucks the artist from the context which nourished his ingenuity. It understates his

training and removes his technical interests from the history of classical

mechanics, a fertile legacy from Aristotle. It overlooks 15th century reliance

on the successes of medieval technology. (Modern science is rooted in the

Middle Ages, not imaginary Renaissance workshops)..

Lastly, it ignores Leonardo’s first hand debt to the inventive hoists, cranes,

and engineering projects of Filippo Brunelleschi, a

Renaissance giant.

That said, as popular heroes go, far better

Leonardo da Vinci than the latest American Idol, Andy

Warhol, or the stock offerings of celebrity culture. At the risk of sounding

corny, the exhibit is nothing short of inspiring. It is designed to excite the

imagination of the young, a prod to put down first-shooter video games and

observe the world.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Workshop at Discovery Times Square Exposition, 226 W. 44th St.,

866-987-9692.

This essay appeared first in CityArts, February 9, 2010.