The Aura of Authenticity

Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Maureen Mullarkey

“I’m going to fix up everything just the way it was before.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

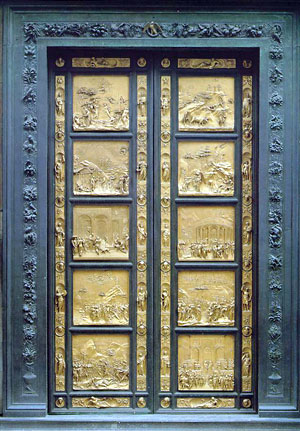

LORENZO GHIBERTI, TRAINED AS A PAINTER AND GOLDSMITH, spent nearly a quarter century creating the gilded bronze doors installed in the eastern portal of Florence’s San Giovanni Baptistery in 1452. More than 500 years later, conservators spent as long relieving them of their place in time. Cleansed of decay and forever young, three of the doors’s narrative panels went on tour this spring in Atlanta, then Chicago, and on to the Metropolitan at the end of October.

|

| Gates of Paradise, Lorenzo Ghiberti |

Inevitably, the exhibition is a press event and an obligatory museum experience. Installed in the 16th century Vélez Blanco Patio, it is also a poignant exercise in cultural estrangement in which the aura of authenticity trumps authenticity itself. But first, the doors.

Andrea Pisano designed the first set of bronze doors for the building’s southern portal in the 1330s. Its Gothic-style bas-reliefs depict the life of John the Baptist, Florence’s patron saint, plus personifications of the theological and cardinal virtues. In 1401, Ghiberti won a commission against Filippo Brunelleschi, among others, to fashion doors for the eastern portal. (Donatello was too young to compete but assisted in the victor’s workshop instead.) Following Pisano’s precedent, Ghiberti illustrated the life of Christ on twenty eight quatrefoil reliefs.

A year after completing the first commission in 1424, he contracted for another pair representing scenes from the Hebrew Bible. By 1452, with all but the gilding done, these doors were so admired that Ghiberti’s initial set was moved to the northern entrance to make way for his ground-breaking encore. It is this third set we know today by the name Michelangelo, quoting Genesis, gave it: “porta caeli.” The Gates of Paradise — Jacob’s description of the ladder of angels seen in a dream.

The Gates rank among the defining achievements of early Renaissance art and were an enduring influence on Italian painters and sculptors for generations. They represent the flowering of that remarkable combination of ars and scientia that crystallized in fifteenth century Florence.

On this last set, Ghiberti condensed his narrative to ten panels using a larger square format that permitted many more figures and room for experimentation with proportion and spatial depth. In the manner of medieval pictorial narrative, each panel combines several episodes related to the central drama. Yet the effect is of unbroken consonance. Figures, carrying the poses of Renaissance painting, move through beautifully interlocked arcades or successions of hills that recede in ever-finer relief. Space itself becomes a subject of these panels.

Unhappily, curatorial interest stops there. Empathy and a theologically literate grasp of history — what Leo Steinberg brought to his study of the Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance art — impinge not at all on the exhibition’s veneration of technology. What did these doors mean in the circumstances in which they were made? That is nonessential to a project admittedly intended to promote tourism and Italy’s restoration industry.

Relics are mute and require intercession to give them voice. But the exhibition and its supporting scholarship keep mum on everything but the material concerns of technicians. Historian David Lowenthal’s words apply: “Unwilling or unable to incorporate the legacy of the past into our own creative acts, we concentrate instead on saving its remaining vestiges. The less integral the role of the past in our lives, the more imperative the urge to preserve its relics.”

His comment resonates pointedly in the wake of the European Union’s reluctance to acknowledge its Judæo-Christian heritage. Technology gets better and better at rescuing objects that represent an ethos no longer recognized.

The Gates of Paradise bespeak the biblical wakefulness that leavened Renaissance humanism. Man was becoming the measure of all things, but he still knew himself to be made “in the image and likeness” of God. The beauty and harmony of classical proportions was understood to reflect the perfection of divine order, a vital concept in Renaissance ateliers. Virtuosity was not mistaken for the substance of culture nor substituted for it.

Severed from their purposes as sacred architecture, Ghiberti’s panels are on tour as capital assests, pay-per-view spectacles in a techno-secular world. They are presented solely in terms of the inventory of techniques that created them and those that restored them. Recognition of the Baptistery as a symbol of communal identity, a shared history inseparable from the particulariy of the West, is inadmissable.

When Ghiberti wrote that he worked on the Gates “with the greatest diligence and the greatest love,” he referred to more than lost wax processes and linear perspective. Ghiberti understood his commission as service to the liturgical function of the Baptistery. Yet scholar Andrew Butterfield takes “this extraordinary remark” to suggest only that the design “took considerable time.”

Ghiberti’s choice of biblical episodes earns no attention beyond a slight nod to storytelling. The book Abraham Heschel called “the fountainhead of the finest strivings of man in the Western world” is on the shelf with Anderson and Grimm. The three panels on loan — Adam and Eve, David and Goliath, and Jacob and Esau — are emptied of meaning by exclusive emphasis on planishing punches, chasing tools, burnishers, liners, talk of mercury evaporation, philology, laser technology, and so on. Fidelity to minutiae is trumpeted as a bona fide of authenticity while the spirit goes begging.

The animating character of artifacts from the past is a matter of inquiry that penetrates deeper than technique. But to tourists sipping Bellinis on the Piazza della Signoria, Adam and Eve signifies no more than Rumpelstiltskin. Yet the myth of the Fall, inscribed by Ghiberti in low relief behind the dominant Creation, is the primordial Judæo-Christian stay against utopianism and the scandal of false promises.

Ghiberti’s David beheads Goliath in full foreground relief. The Davidian saga, a tall tale to moderns, speaks eloquently to peoples uninclined to accept the predominance of the West. They know a giant can be felled with box-cutters. Jacob and Esau? Birthrights are sold for a bowl of soup in myriad disguises: cheap consumer goods, multicultural creeds, the kindness of Grand Inquisitors. The list is long.

In our ever-expanding present, the past is a spare-parts warehouse that furnishes spectacles for the tourist trade. Anna Mitrano, pitching for the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence’s heritage complex, states candidly that the exhibition provides publicity for the Opera’s holdings and the expertise of Italian restorers. It is an opportunity, she adds, “to promote the Florentine Renaissance to an American audience.” (In other words, do not let the euro keep you home.)

Ms. Mitrano forgets that Ghiberti’s paradise was regained for Americans over forty years ago. In the late 1950s, San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, a neo-Gothic Episcopal structure then under construction, commissioned replicas of the doors from molds made in the 1940s by Florentine foundry master Bruno Bearzi. When the cathedral was completed in 1964, Time Magazine marveled that the meticulous replication, studiously directed by Bearzi, was closer to mint condition than Ghiberti’s originals.

On their return to Florence, the original panels will be reassembled and preserved — doors to nowhere — in a hermetically sealed case in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. A second edition of duplicates, also made from Bearzi’s molds and discreetly substituted for the originals four decades ago, will stay on the Baptistery.

The future of the mummified doors recalls Hergé’s last, unfinished story, Tintin and Alpha-Art. Enterprising Tintin arranges to have his body embalmed in liquid polyester, signed and authenticated by a famous sculptor, then sold to a collector or museum.

Hergé understood the culture industry better than most.

“The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Renaissance Masterpiece”

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Tel. 212-570-3951).

A version of this essay appeared in The New Criterion, December 2007.

Copyright 2007, Maureen Mullarkey