Under the Sheets with Four Impressionists

Review of Jeffrey Meyers’s “Impressionist Quartet: The Intimate Genius of Manet and Morisot, Degas and Cassatt;” plus Barbara Grossman at New York Studio School

by Maureen Mullarkey

Addressing a D.H. Lawrence conference in 1990, Jeffrey Meyers confessed to boredom listening to Lady Dorothy Brett reminisce at length. All he wanted to know was: “Did you screw John Middleton Murray in 1919”? So, Reader, the questions before us today are: Did Edouard Manet schtup Berthe Morisot? And why was Mary Cassatt left to die wondering, as they used to say?

|

| The Bath, Mary Cassatt |

Admit it, you’d love to know. So would Jeffrey Meyers. The fact that he does not is no bar to writing as if he did. In postmodern biography, norms of truth and deception are determined by expedience. Lack of verifiable evidence need not inhibit marketable conclusions. And as Mr. Meyers instructs us, there are countless ways of begging the same question in one book.

Seriousness fizzles in the opening boilerplate: “…the Manet-Degas circle of painters, the greatest concentration of artistic genius since the Italian Renaissance, created a new way of looking at the world.” Nonsense. Impressionism created a new way of looking at art. The fields of Gennevilliers, irrigated with sewer water, still stank no matter how idyllic Morisot’s paintings of them.

A petri dish for revisionist and experimental theorizing over the last 30-plus years, Impressionism is simply the most discussed, best known and currently most popular movement in the long history of Western art. It inherited a vigorous development of pictorial means—freer brushstrokes, fresh depiction of light and atmosphere—from earlier painters, particularly Courbet and other French Realists. Mr.Meyers’s hyperbole is the first in a catalogue of rhetorical feints, sweaty generalizations, red herrings and other misleads aimed at shrinking the complex milieu of Impressionism to the conceptual limits of a supermarket tabloid.

Anxious to arrive at a sexual liaison between Manet and Morisot before her marriage to his brother Eugene, the author thumbs a ride on every innuendo he can find. His standard of evidence runs to insinuation, wishful thinking and special pleading. A parade of “might have”s, “may have”s, “could have”s, “must have”s and “seemed to”s displaces the burden of proof onto the audience. Without means to disprove the assertion of a sexual affair, hapless readers assume it must be true.

Was the illegitimate son of Manet’s wife Suzanne his own, as scholars suspect but cannot verify? Or should we trust this author’s assertion that “there is strong evidence to suggest” Manet’s father sired the boy? Suggestions are not evidence. No martyr to verifiable data, Mr. Meyers leaps to suppose: “Manet may have inherited his father’s mistress as well as his fortune.” This conjecture is crucial to a subsequent one: his surmise that maybe Manet similarly passed off Berthe Morisot on Eugene. One shot in the dark boosts another, and distinctions between hunch and plausible history dissolve.

After Manet’s death, Morisot referred warmly to her “old bonds of friendship with Edouard” and remembered “the days of friendship and intimacy with him.” In Mr. Meyers’s lexicon, intimacy has only one connotation, inflatable into proof that Manet “inspired her love.” Wink, wink.

After her husband’s death, Morisot wrote: “I should like to live my life over again, to record it, to admit my weaknesses… I have sinned, I have suffered, I have atoned for it. “That, unexceptional in context, is the consummation toward which so much heavy breathing has been aimed. It is the evidential high point, transforming previous guesswork into incontestable fact:

“Berthe . . . had sinned by sleeping with Edouard and atoned for her sin by marrying Eugene—just as August Manet had once sinned with Suzanne and Edouard had atoned for his father’s sin by marrying her.”

Every grieving spouse suffers litanies of remorse for things done and left undone, but Mr. Meyers ignores alternative interpretations. Of the seven deadlies, he recognizes only one, nailing every ambiguity to the bedpost.

Is it likely that a wealthy, married, socially prominent syphilitic like Manet would chance a sexual affair with a woman of his own station and social circle? How readily would a woman of Morisot’s position—before reliable contraception and safe, clinical abortion on demand—risk her social standing and economic well being? Mr. Meyers conflates Paris in the 1860s and ‘70s with Bloomsbury in the 1920s or his native Berkeley, 2005. The anachronism is obvious but so what. Just look how Manet’s paintings of Morisot—those eyes! the disheveled hair! the sexual tension!—illustrate “the impossibility of their love.” Mr. Meyers writes like Barbara Cartland imitating Fernand Braudel.

If Morisot is the heroine of this revisionist romance, Cassatt is the crone. Her linen was clean; the rest is dross to Mr. Meyers. With no bedding to examine, he is faced with her art and the strength of her career. He shortshrifts both, obedient to contemporary feminist preference for the weaker Morisot.

Pupil of Corot (a frequent guest of the Morisots), friend and sister-in-law of Manet, wealthy salon-goer and hostess to the cultural elites of her time, Morisot was exquisitely placed for achievement and recognition. Yet she never produced a body of work the equal of Cassatt’s. Emigrating alone to Paris, Cassatt lived her adult life as a largely self-supporting, unmarried woman—notwithstanding the author’s description of her as “sheltered.” She managed a career on both sides of the Atlantic, helping support her parents and aiding other Impressionists. She prevailed in a man’s profession despite being marked as a foreigner in France, and was more successful in her lifetime than Morisot.

|

| Mary Cassatt |

What accounts for the difference in achievement between these two women? Our biographer is not seriously interested in getting under the skin of his subjects or their times; he prefers to get under the sheets, if only to play peek-a-boo. To Mr. Meyers, Degas’s celibate dedication to his art is admirably monastic; Cassatt’s is symptomatic of sexual repression and lack of sex appeal. He considers her subject matter—women and children—irrefutable compensation for frustrated sexuality and thwarted maternity. Yet the most famous practitioner of mother-child themes in the era was Eugene Carriere; and it was Utamaro’s images of women—together and with children—that resonate so profoundly in Cassatt’s work.

Mr. Meyers has little interest in art history, exigencies of craft or habits of working. He cares more that Cassatt was not pretty, possibly had “a big behind” and, in old age, had hollow cheeks and “clawlike” hands. What she did with those hands is tertiary to her lack of interest as a subject of sexual intrigue and her usefulness as a foil to the sainted Morisot. He has an unhelpful habit of using the terms “her [or his] biographer” without specifying which one when there are several. Worse, he embellishes his narrative with extraneous literary allusions—to Proust, Tolstoy, D.H. Lawrence—that lend tone to speculation, disguising it as scholarship.

Cherry-picking secondary sources for manipulable quotes, Mr. Meyers is not reconstructing lives but narrowing them to fit the demands of mass market voyeurism. This reductive, unnecessary book is directed toward the casual reader, the one with fewest defenses against authorial sleight-of-mind. It leaves you sympathetic to Virginia Woolf’s judgment of biography as “A bastard, an impure art.”

This review appeared first in The New York Sun, June 2, 2005.

Barbara Grossman has achieved substantial recognition over the three decades of her exhibiting life. The reasons why are on view at the Studio School, the fourth and final stop of a traveling exhibition of painting, oil pastels, monoprints and drawings. It is accompanied by a well-illustrated brochure with an essay by painter and critic Hearne Pardee.

|

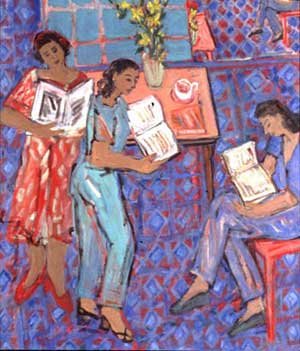

| Sisters Singing |

Calling the work “radiant and expansive,” Pardee gets to the heart of Ms. Grossman’s appeal. Here are color and pattern for their own sakes yet still tethered to the human figure in domestic interiors. Her figures—languid women in variegated dress—are less references to the real world of parlors and dining rooms than pretexts for juxtapositions of pattern and color harmonies. Even skin color surrenders its cue as a racial reference, providing either a contrast against background color or a means of sinking the form into the value range behind it.

I did not know Ms. Grossman’s work in the 1970s. For me, the surprise of this show is the earlier work and what it reveals about the creative decisions she has made. “Apple Tree” (1976) is a lovely charcoal that places the rightward droop of a branch in the exact spot the composition requires to fill the page as gladly as possible. The architectural emphasis of the bare tree provides accompaniment to the clear, schematic building lines of “Bassett Road House” (1976). Her attention to structure is still fully apparent in “Louise in Rocker” (1976), an oil that presages her chromatic skills but retains the spatial elements of firmly realized planes.

Ms. Grossman’s increased attachment to an overall design—in the abstract expressionist sense—is most apparent in the oil pastels and monotypes. Here, figures melt into their backgrounds; one textile evocation slides into another like the parts of multi-hued batik print. Constituent parts rise to merge into a single prevailing pattern. This building up of pattern in ever-increasing complexity is attractive on its own terms; but it risks surrendering the psychological overtones that accompany figures in groups—what Graham Nickson called the “conversation” between these women.

Going forward, it would be good to see Ms. Grossman reassert her own linear grace and clarity. By re-establishing structure, attending more closely to it, she would strengthen the coloristic rhythms and harmonies she has chosen to emphasize. More precisely, it would observe the distinction between composition and decoration. The first applies to the establishment of structures, the other to their elaboration and and enrichment. Gombrich reminds us that, in music ornamentation has no effect on harmonics, on the progression of chords. It remains an embellishment, a grace note. In painting, too, grace notes exist to serve the composition, not to conceal it.

“Barbara Grossman: A Survey” at New York Studio School, 8 West 8th Street, 212.673.6466.

This review appeared in ArtCritical, June, 2005.

Copyright 2005 Maureen Mullarkey