Verace Pinto, Two Ways

Marc de Montebello at W.M. Brady & Co.; Luciano Ventrone at Bernaducci.Meisel

By Maureen Mullarkey

BORN IN ROME IN 1942, LUCIANO VENTRONE is a celebrated Italian photorealist with a distinguished exhibition history centered in Rome, Milan, and Bologna. This is his first solo show in New York.

He came of age in tandem with Richard Estes, Robert Cottingham, Chuck Close, and other first-generation photorealists but he takes a very different turn from his American counterparts. Mr. Ventrone uses the techniques of the genre to bypass mundane contemporary items and quotidian scenes. He anchors his imagery in the tradition of Italian still life painting that dates back to Caravaggio.

|

| La Mestra e l'orgoglio, Luciano Ventrone, 2007 |

More than photorealism was in the Italian air in the early Sixties. Mr. Ventrone held his first exhibition in Rome in 1963, the year Roberto Longhi published his groundbreaking studies of Caravaggio’s influences and effect. His second show followed in 1964, a year that galvanized artists and scholars alike with the great exhibition of Italian still lifes held in Naples and traveling afterward to Milan, Rotterdam and Zurich. On show at Bernaducci.Meisel is Mr. Ventrone’s persuasive reconciliation of these two disparate strains of motivation, one from the late Renaissance and the other from his own formative period.

“Satelliti” (2007-8), “Allegria Irrequieta” (2008) and “Vincere il Tempo” (2--7-8) are unabashed paraphrases of Caravaggio’s “Basket of Fruit” (c.1596), in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan. Here are the woven baskets, fruits piled on top of each other under a crown of crisply outlined, blighted grape leaves and a trail of vine. “Il Dona della Natura” (2008) repeats the motif minus the wicker basket. Fruits spread across a flat white surface in a decorative display of market abundance that imitates traditional table top scenes.

But tradition comes with an unmistakably modern, even theatrical, twist. It is viewed under the powerful artificial lighting that belongs exclusively to the 20th century. Raking overhead lights remove the motifs from Caravaggio’s visual world and place them squarely on the front lines of contemporary food styling.

Mr. Ventrone photographs his own setups and arranges them with the precision of a stylist for Gourmet. Fruits split open to announce their ripeness. Mr. Ventrone repeats the cleft pomegranates and breaking melons that make the paintings of Giovanna Garzoni (1600-70) so engaging. (Garzoni was one of the loveliest rediscoveries in the 1964 Naples exhibition.)

“Scarlet Lake” (2008) and “La Maestra e l’orgoglio” (2007) are particularly appealing. One cluster of fruit fills a crazed Chinese bowl; another rises up from an unglazed ceramic piece decorated with mythological figures. Each spare, deliberate alignment of these fruits and stems approaches the formal restraint of ikebana. Mr. Ventrone is most satisfying when his structuring impulses guide decorative ones.

And It is form, not contrived enticement, that is the real pleasure of these compositions,. None are any more hyper-real for their time than Caravaggio’s verace pinto was in his. If photorealism seems to give us more to see than 17th-century realism provided, that is because our viewing is heightened by newer systems of lighting. Candle power suppresses minute detail; multiple 500-1000 watt bulbs exaggerate it, even without a macro lens. The artist’s challenge is to hang on to form amid a welter of exposed detail. And Mr. Ventrone does.

“Il Bianco della Spose” (2008) masses the heads of white roses, in full bloom, in a pale marble bowl against a gray backdrop. It is a simple arrangement but also a study of light that diversifies tonalities within the single color, emphasizes volumes and distinguishes textures. “Sci di Colore” (2008) does the same but with a more varied blend of colors and shapes. Studio light, entering from more than one direction, grants each aggrandized petal its own spatial dimension. By canceling out chiaroscuro, it bypasses romantic moodiness. For all the prettiness inherent in the motif, these are clinically unsentimental floral pieces.

“Crollo Nervoso” (2008) is a strangely violent image. A watermelon is shattered into pieces and a few seeds scattered about. The rind is just beginning to dry and shrivel; chunks of flesh hang loose. Rot is not far off. Full-spectrum lighting glistens on the moisture of the fruit as it would on the bloody pulp of a fresh road kill. Set against a dense black background, it is an unsettling illustration of the way metaphors for death assert themselves in unlikely places.

The slick surface and artifice of photorealism do not favor figuration. Four female nudes are included, each one another luncheon piece. Studied poses, Ingres-like turbans and faux modesty—that coy hint of shaved pubis—evoke the refined vulgarity of soft-core calendar girls. Woman-as-ripe-fruit is a tired trope.

It is hard not to imagine these figures sprayed with glycerin and set, like lamb chops, on a bed of scallions. Bartelo Pisanelli, Caravaggio’s contemporary and food writer, declared scallions had no purpose than “to excite the libido.” Just so. Mr. Ventrone’s still lifes look more convincing without them.

“Luciano Ventrone: The Eternal Present” at Bernaducci.Meisel Gallery (37 W. 57 Street, 212-593-3757).

For Marc de Montebello, art is the family business. His father, Phillipe, recently retired as the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for three decades. In 1991, he opened his own gallery, which specialized in 19th- and early 20th century works, on East 84th Street, down the block from his father’s office. He closed the gallery in 2000 to concentrate on his own painting.

Mr. de Montebello’s grandfather, a scientist and painter, introduced him to painting early. The introduction stuck — and to good effect. His first solo show at W.M. Brady & Co., just three years ago, sold out. The 44-year old is an engaging painter with a cultivated eye and a palette to support it.

|

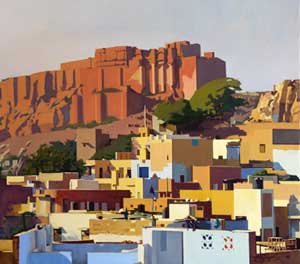

| View of Jodhpur, Marc de Montebello, 2008 |

The artist’s second show, “Small Pictures,” is full of unassuming delights. The show comprises approximately forty plein air landscape paintings, most of them nearly diminutive in size. Subjects include New York, Maine, California, Canada and India, as well as views of the interior of the artist's New York studio.

Capping the ensemble are two surprising, large-scale landscapes. One is a lyrical, semi-abstract panorama of the north shore of Frenchman Bay, Maine; the other, a rigorously designed view of Jodhpur’s ancient cliffside Mehrengarth Fort seen from modern dwellings below. The poise of both paintings derives from Mr. de Montebello’s agility in combining expressive color with crisp contours that emphasize the particularity of place.

He once described his own work as "sort of a cross between Corot and Fairfield Porter." It is a serviceable assertion that names his closest influences but it does not do justice to the distinction of his own sensibilities. These are fully on view in the two large canvases here — not because of size itself but because the larger format allows a developed analysis of his motif and gives free reign to his hand. And Mr. Montebello has a very good hand.

He holds Corot’s affection for the pochade — that quick, freely handled sketch on a small panel that fits within a portable easel. But more significantly, Mr. de Montebello, like Porter, is concerned with things, not ideas. What matters is what is in front of him. The immediate experience of seeing a particular place or thing in a certain light and from a particular vantage point is the painter’s sole concern. An appealing modesty attaches to these understated miniatures.

Some of the smallest oils are also the loveliest. “Barge, Hudson River”

(2005), divides the 4-inch high composition into a series of horizontal bands in a subdued key. A slender line of clear red, marking a barge interior, breaks the calm of the foreground. Tints of the same hue, bleached and grayed, dot the dock containers aligned across the middle ground. “Landscape, Rajasthan” (2006) bears the tonal persuasion that comes from study of Corot’s plein air greens and sandy neutrals.

Two paintings of buoys in Bombay Harbor dissolve into mist, Here, atmospheric obscurity transforms a commonplace object into an enigmatic emblem of quietude. A gem of felt observation, “Hudson River, Late Afternoon” (2006) captures the cool tones of dying light. Each image of Hancock, Maine, carries the same conviction. The motifs speak for themselves, without style-consciousness imposed on visual reality.

Mr. de Montebello’s smaller works are intimate in the best sense. They convey an impression of having been made for the artist himself, in solitude. The two large oils here — ”Frenchman’s Bay, Looking South” and “View of Jodhpur” — are more ambitious in conception and execution. Drawn with great discernment, each belies Porter’s insistence that contour is secondary to light and color. Both paintings are impressive and seductive.

“Marc de Montebello: Small Pictures” at W.M.. Brady & Co. until (22 East 80th Street, 212-249-7212).

These reviews both appeared first in The New York Sun on May 8, 2008.

Copyright 2008, Maureen Mullarkey