Nothing Left to Hide

“Why the Nude?” at the Art Students League; Jacob Collins’ nudes at Hirschl & Adler

By Maureen Mullarkey

THE NUDE IS A SIGN SYSTEM THAT SIGNALS ITS MILIEU more legibly than any other genre. More transparent than even portraiture, the nude exposes both its creator and the culture of its time. Sculptor Barney Hodes is right: “It’s not just the model who has nothing left to hide.”

|

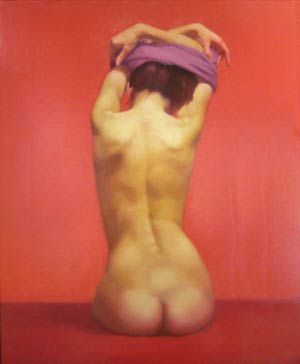

| R Undressing, Sharon Sprung, 2006 |

“Why the Nude? Contemporary Approaches” is the Art Student League’s annual curated exhibition. On display are some 50 works by League instructors and, for the first time, outside artists. The name-conscious range of approaches yields an omnium gatherum of irreconcilable sensibilities, plus a few insensibilities.

Work runs the gamut from William Beckman’s drawing of his bride stripped bare to Knox Martin’s wiseacre abstraction. The reticence and pictorial intelligence of Mary Beth McKenzie and Alan Feltus vie with Will Cotton’s fairy floss. Names pile up and and fine work gets lost in the contemporizing clutter.

Kenneth Clark’s distinction between the naked and the nude is largely bypassed in favor of nakedness and its discontents. In Clark’s lexicon, the nude is an ordered design that is less the subject of art than an essential structure. Contemporary artists prefer nakedness itself, a pinch-hitter for deeper disclosures. Few contemporaries accept the nude as a form entrusted to them. Most often it is an opportunity for irony or for pulling knickers down. Or yanking up a skirt, as Martha Bloom does in “Sea Sighting” (2006).

“Hangin”’ (2002), Denise Marika’s video of an armless, headless nude swinging overhead, is typical of the aimlessness that afflicts much contemporary figuration. It is a flickering rewind of Joan Semmel’s cropped females, ungainly darlings of the 1970’s feminist art movement. Ms. Semmel’s “Pink Cushion” (2004), in turn, mimics Philip Pearlstein, whose predictable signature hangs nearby.

Francis Cunningham’s and Sharon Sprung’s paintings are among the few that seek reconciliation between a living organism and an art of measure. Mr. Cunningham’s “Regina Hawkins” (2005), a monumental standing figure, is beautifully poised between the actual and the ideal. The large, calm planes of a particular female body assume the stateliness of classical motifs on the model’s platform. (Revisit Henry James’ short story “The Real Thing,” and the painting will resonate in unexpected ways.)

Ms. Sprung’s “R Undressing” (2006), a seated nude seen from behind with arms raised, recalls Rubens’ drawing of a model disrobing. Rising in balanced rhythms from buttocks to shoulder girdle, the figure succeeds as a warm-bodied reminder of Clark’s insistence that “the bottom is a baroque form.”

Sensitive to mass and volume, Mr. Hodes brings Rodin’s aims into the present with a glazed, fragmented female torso. For all its wanton bulk, there is poignancy to this gritty, tactile body. Unconfined and over-fleshed, struggling against gravity and time, it evokes Erasmus’ warning that “mortal life is nothing but a kind of warfare.”

Judy Fox’s “Krishna” (2001), a life-sized ceramic sculpture of the Hindu god, marries an hieratic prototype to a contemporary model. Cross-legged and sylphic, the reclining youth plays an invisible flute. His quiescent sexuality is the more unsettling for its seeming artlessness, innocent of seductive intent. It is a relief to see Ms. Fox’s beautiful surfaces applied to something besides her celebrated 7-year old nudes with their Jon Benet Ramsey frisson. The demonic, too, can come to us as loveliness and ease.

Ultimately, what matters most is the sensibility that informs expertise, the motive sustaining the method. That brings us to Jacob Collins, the Ralph Reed of a secular revival culture built on the gospel of traditional art practices. Mr. Collins evangelizes for something dubbed Classical Realism, which contains neither classicism nor realism as Courbet understood it. Rather, it promises deliverance from the tribulations of modernism and restoration of Art as it was in the beginning, is now and ever shall be.

Realism is not a style but a response to life, its content and condition. Classical Realism, by contrast, is a contemporary style with retro appeal—like Chrysler’s PT Cruiser. Though addressed to a different demographic, it is as much a marketing phenomenon as Thomas Kinkade’s Paintings of Light. Mr. Collins, like Kinkade, casts a line to audiences who see themselves as a chosen remnant recovering a lost ark.

The publicist’s blurb took care to note that the artist “lives in an upper East Side Manhattan carriage house.” The cue is irrelevant to painting but crucial to the self-conscious aura of staged refinement that is the real content of the work.

“Anna,” “Candace,” and coyly posed and lighted couples are McNudes for the carriage trade. This is fastidious erotica to go with the Jado bidet and high thread-count linens from Yves Delorme. [You can inspect the sheets in “Unmade Bed” (2005).] Good living and good nipples are the classic combo in “Reclining Nude” (2006). The nudes are less a counter to the vacancy of contemporary culture than an extension of it.

Love of the figure as a significant form differs from the conceits of an artificial return to classicism. Humility before the motif, a precondition to love, is absent from all but Mr. Collins’ portraits. Undeniably fine, only these are inhabited. The dynamic specificity of a face overcomes eroticizing intent and mannerist display to serve individual character.

Dying arts of the past have been resuscitated regularly since Charles Eastlake’s authoritative study of Old Master materials and techniques appeared in 1847. As the League makes plain, skills survive. Yet we still cannot create on par with the Florentines or Venetians. Lost methods matter less than forgotten frames of reference, abandoned conceptions of man and his purpose. Our practices are subordinate to who we are.

“Why the Nude? Contemporary Approaches” at The Art Students League (215 West 57th Street, 212-247-4510).

Jacob Collins: Figures” at Hirshl & Adler (21 East 70th Street, 212-535-8810).

This review appeared first in The New York Sun, October 12, 2006.

Copyright 2006, Maureen Mullarkey