With Nothing to Prove

Elizabeth’s O’Reilly’s painting and collages at George Billis Gallery; Alexandra Athanassiades’s sculpture at Kouros Gallery; also Sam Fogg LTD. in New York City

by Maureen Mullarkey

“THANK HEAVEN FOR ART THAT HAS NOTHING TO PROVE” wrote Louise Bogan. I cannot look at Elizabeth O’Reilly’s lyrical celebrations of unexceptional sites without thinking of Bogan. Poetry editor of The New Yorker for many years and a poet herself, she understood that art fulfills its purposes on the aesthetic plane alone.

|

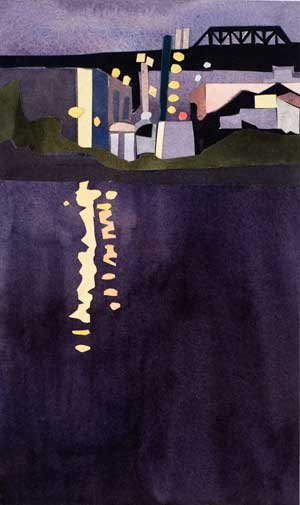

| From 3rd St., Night, Elizabeth O'Reilly |

Elizabeth O’Reilly’s current exhibition at George Billis Gallery displays a generous selection of those freely-brushed plein air landscapes for which she is known. But there is a delicious surprise in this show. Her paintings — scenes of Vermont, Maine, and Long Island’s North Fork — are accompanied for the first time by watercolor collages of Brooklyn that lend a distinctive modernity and sophisticated whimsy to her motifs.

Among the paintings, “Cushing Bridge” is particularly deft and lovely. The rigid structures of a rural trestle bridge cut into view on a diagonal. Shimmering reflections of the green-painted steel beams flow rhythmically downward across the surface of a narrow river. Descending movement links the bridge to the foreground of the picture plane while, at the same time, it conveys the reality of a moving current. That sense of fluid motion acts dynamically on both the abstract and representational levels.

“Double Road, North Carolina” makes similar pictorial use of shadows across a road. The shadows quaver out of fidelity to the irregularities of the trees that cast them and in response to dips in the road. The effect, again, is of movement. That, and lively exaggerated color, lend savor to an ordinary country road. Ms. O’Reilly’s bravura is evident in the point from which she chose to view it — just where a turnoff from the main road heads off to the right. Separation of the diverging planes is handled so simply and convincingly that you do not notice the difficulty of it.

Unafraid to experiment, Ms. O’Reilly has taken up watercolor again after having abandoned it some years ago. The results are captivating. Despite its popularity as a plein air medium, watercolor is obstreperous. Fluidity impedes efforts to control color, degree of saturation and placement on the page all at once. Ms. O’Reilly short-circuited these obstacles by taking a technical hint from the small collages of Alex Katz.

She separates color and shape into two distinct processes. Once her wash achieves the desired tone, she cuts into it, drawing with an X-Acto knife. This substitutes crisp, decisive edges for the painterly gradations of a brush stroke. Subtle angularities displace curves, carving unexpected character into loose forms accustomed to the wandering caress of a brush.

“From 3rd Street, Night,” “Carroll Street Bridge,” and “Dusk” are magical images. Shaped by a knife, clouds and points of light — often indefinite — take on irrevocable contours. And all have that sense of play inherent in cutouts.

ALEXANDRA ATHANASSIADES WAS BORN IN ATHENS where she still lives, works and exhibits. “Horses & Armour,” her second solo appearance at Kouros Gallery, is subsequent to an exhibition earlier this year that was sponsored by the European Cultural Centre of Delphi, Dephi, Greece.

Two very distinct bodies of work are included here. One is derived from the ancient Greek lorica musculata or muscle cuirass, one of the earliest forms of body armor. Dating back even to the Etruscans, it was typically worn by Greek infantry in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.

|

Armour XII, Alexandra Athanassiades |

The other is a series of horse shapes made from the twisted forms of tree limbs. Both series are characterized by her Greek roots; both are open to interpretations that transcend their Greek character.

Her bronze and iron cuirasses are particularly powerful. All repeat the finely articulated musculature of their ancient models. Greek cuirasses — like the later, more embellished Roman ones — provided a sensitive rendering of the male physique. Made to fit the human torso, the cuirass reproduced the anatomy of the male chest and upper abdomen, often in meticulous detail.

Ms. Athanassiades seizes the essential lineaments, omits minutiae and distresses the surfaces. Her adaptations draw strength from exquisite manipulation of the texture and torn edges of the given form. Cuirasses split at the sides, as if from age or violence. In one, thin layers of steel peel back in delicate evocations of skin, torn flesh or simply the natural history of decay. In another, the form seems to burst open from within, heightening intimations of violence. Each breastplate bears wounds, either of time or the cruelties of history. However you understand them, the elegiac and funerary implications are unmistakable.

The horses are different in tone and handling. She constructs them of random materials, combining found pieces of natural wood with delicate ribbons of steel to emphasize equine anatomy. These are not so much sculptures as assemblages enhanced by surface manipulation. Her individual horse’s heads are wonderfully convincing, all mass and charged movement. “Horse LXXII” (2007) twists upward from a charred neck with persuasive animal vitality

Less successful are the three-dimensional contour sketches, so to speak, of horses whose hollow outlines are strung together from found pieces of tree limb. Only “Horse LX” (2005), affixed to metal fittings and with wheel like a carriage frame, has life to it. A witty arrangement, it suggests a 4-wheeled cock horse or a nursery variant of the mother of all hobby horses, the Trojan one.

Others are formless and piecemeal, lacking the aesthetic justification of the energetic and richly expressive heads. Taken together with the drawings on view—two surprisingly vague studies of the Parthenon frieze— suggest that Ms. Athanassiades’s gift for exploiting already existing forms is greater than her capacity to shape new ones. But that is nothing against the beauty that she wrings from her materials.

“If the mountain will not come to Mohammed…" No, wait. That starts the wrong way around. Sam Fogg Ltd. is the mountain. And it is coming to you from London’s West One on October 18th.

Sam Fogg is one of the world’s leading dealers in medieval art. A visit to his incomparable stock ranks high on the itinerary of knowledgeable travelers. Located on the top floor of the Colnaghi building just off Bond Street, the showroom is a Dickensian cross between Westminster and the British Museum. Anyone enthralled by medieval manuscripts and illuminated calligraphy of various kinds — Russian, Armenian, Asian, Islamic — finds their bliss at Sam Fogg’s.

Exhibiting his wares in the United States for the first time, he has staged “Art of the Middle Ages” at the uptown Alexander Gallery through November 2. The exhibition includes precious objects, sculpture, stained glass, manuscripts and paintings. It coincides with another distinguished exhibition, “Collecting Treasures of the Past, VI”, held by Anthony Blumka and Florian Eitle-Böhler, of the Munich gallery Julius Böhler, at Blumka Gallery, 209 East 72nd Street.

On display are such treasures as a small 9th century Anglo-Saxon casket made of oak and gilded with copper and silver. Two wonderful pieces from Nuremberg are here. One is a delicately carved mother-of-pearl tabernacle dated 1499; the other is a painted panel by Hans Süss von Kulmbach, Albrecht Dürer’s best pupil and successor. A composite panel of 15th and 16th century stained glass is a suite of fragments painstakingling reassembled by a 19th century collector.

Boasting an unbroken provenance of nearly 1,000 years is an 11th century giant Bible from the Rhineland. This huge manuscript on vellum is considered the oldest existing one-volume Bible of any kind from Germany.

A velvet Cloth of State, made for Isabella of Castile at the end of the 15th century, was probably intended to decorate a throne during festivals or high state occasions. Intricately stitched with gold and silver thread, it is a gorgeous example of the heraldic embroidery and appliqué which died out with the nobility who commissioned it.

Sam Fogg is here, of course, for your money. With sale prices ranging from $10,000 to $5 million, the exhibition bills itself as “a splendid opportunity for museums and collectors to acquire major pieces in New York this autumn.” If you are just looking, all the better. Then you will not have to fret over red-flag phrases like “probably preserved in Mossac Abbey” or “newly discovered”

The Alexander Gallery can seem an intimidating place. Wear good shoes and, if you must, pretend you are doing field work for The Robb Report.

“Elizabeth O’Reilly: Painting & Collages” at George Billis Gallery (511 West 25th Street, 212-645-2621).

“Alexandra Athanassiades: Horses & Armour” at Kouros Gallery (23 East 73rd Street, 212-288-5888).

“Art of the Middle Ages” presented by Sam Fogg at Alexander Gallery (942 Madison Avenue at 74th Street, 212-472-1636).

This review appeared first in The New York Sun on November

15, 2007. Copy on Sam Fogg LTD appeared in on November 1.

Copyright 2007, Maureen Mullarkey