Rouault�s Anguished World

�Miserere et Guerre� at the Musueum of Biblical Art

By Maureen Mullarkey

SUFFERING

HAS PROVIDED WESTERN CIVILIZATION with magnificent

works of art. The great Lenten

theme of Allegri�s �Miserere� and Bach�s �St. Matthew Passion�, it fructifies

music no less than visual art. Yet for all its grandeur in successive

historical epiphanies, it seems now, somehow, out of time. Anguish, that dark

night of the soul, is eclipsed by industries created to erase it.

Georges Rouault (1871-1958), one of the most significant painters of his day, married the motif of

suffering to modernist pictorial aims. On exhibition at the Museum of Biblical

Art [MOBIA] are the 58 black-and-white, mixed media intaglio prints of his

series �Miserere et Guerre,� considered his finest achievement. Several

additional works in color provide a fuller sense of his capacities as a

painter.

|

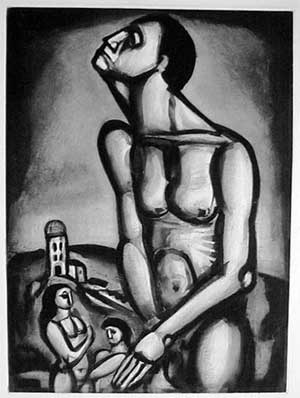

| Georges Rouault, Convicts |

The tenor of this body of

work, steeped in the sorrow of living, is inseparable from Rouault�s personal

history. He was born in a working class quarter of Paris during the bloody end

of the Paris Commune. France had lost the Franco-Prussian War and the city was

under bombardment by government troops determined to quell communards defying

Prussian victory. The weight of massacre and horrific destruction fell on the

working class and the budding French labor movement. The doomed Commune,

followed soon enough by the agony

of World War I, still echoes in �Miserere et Guerre.�

His father, a piano

finisher in a local factory, imparted a craftsman�s love of tools and materials

and ardent social sympathies. His grandfather, a postal clerk and a modest

collector of prints by Caillot and Daumier, encouraged him to become an artist.

Rouault�s hatred of war, identification with the poor, and love of art were

established at the beginning.

His mature work was

marked by early apprenticeship to a stained glass maker and restorer of

medieval windows. A lasting love for the medium is evident in the bold outlines

of his personal idiom, immediately recognizable and evocative. At the Ecole des

Beaux Arts he studied under Gustav Moreau, a leading Symbolist, who prompted

him to seek subjects beyond tangibles—in religion and

philosophy—and trust his own creative subjectivity.

Rouault was intimate with

the writers who formed the nucleus of the Catholic revival, that remarkable

literary, intellectual, and—to a lesser degree—artistic renewal

among France�s lay intelligentsia in the early 20th century. He counted as friends Léon Bloy, J.K. Huysmans and Jacques and Raissa Maritain, both also passionate

supporters of his work. He was close to Georges Desvalli�res,

co-founder with Maurice Denis of the Atelier de l�Art Sacr�.

The Atelier was precursor

to the Sacred Art Movement, a brief effort to reanimate sacred art which French

Catholic intellectuals agreed was in a dismal state. Huysmans wrote brilliantly

on �the hemorrhage of bad taste�

at Lourdes. Maritain similarly rejected conventional religious art as �devilish

ugliness.� Rouault shared their

disdain, fearful of admitting �sullen convention� into his work.

Rouault�s penitential

vision and epic sweep suited the temper of the years immediately after World

War II. MoMA gave him a retrospective in 1945 and the Tate did the same the

following year, pairing him with Braque. He exhibited at the Venice Biennale in

1948 and enjoyed a flood of exhibitions in the 1950s. France inducted him into

the Legion of Honor and, in 1958, gave him a state funeral.

Today, his work is rarely

seen. This exhibition seeks to return it to view. And there is every reason to

keep his accomplishment alive. Rouault was a graphically gifted, fastidious

craftsman sympatheticto a world

in travail. His subjects were few:

clowns, prostitutes, judges, self-satisfied pillars of society, the down-hearted, and the Passion

of Christ. Setting aside religious dimensions, his cast is similar to that of

Lautrec, the youthful Picasso, and Daumier.

A Passiontide sensibility

infuses his oeuvre with a distinctive solemnity. Isaiah�s man of sorrows, the

crucified Christ, serves as an archetype of the human condition. However devout

Rouault�s Catholicism, it is a mistake to pigeon-hole him as a devotional

painter. He used Biblical iconography—as did Max Beckmann and other

German Expressionists—as a source of recognizable metaphors. Every

generation faces its Calvary and crucifixions accompany history. The

lamentations of Jeremiah still resonate.

Rouault spent much of the

years 1914-18 and 1920-27 working on these plates, a project undertaken for his

dealer, Ambrose Vollard. He altered each one, subjecting them to as many as

twelve or fifteen successive states, until he was satisfied with the results. Heavily

outlined figures, lit from within, are worked to a luminous pitch by scoring,

stippling, blotting and wiping of the plates. He mixed soft-ground etching

techniques with engraving, drypoint, and aquatint, pushing for textural and

tonal effects that give the impression of a painted surface.

Texture is a sculptural

element that lends bulk to the drawn image. The beauty ofthe crucified corpus in

Plate 57 lies in the balance of weight thrown into low relief by the distressed

plate. Bold surface effects add steel to the tenderness of Plate 12. Mother and

child press against each other, transfigured into a single block. Inner pressure stretches the

child�s head upward, like a fledgling�s in the nest, toward the mother�s bent

face. As an image of love, human or divine, it is matchless.

Several of his bitterest

designs have a Germanic flavor. The fat-faced figure of �Far from the Smile of

Reims� sports the Prussian eagle on his helmet plate. Or is it the Holy Spirit

on a bishop�s mitre? Prussian general or ecclesiastical bureaucrat, the image

is a jeremiad against inordinate pride. The �haughty scorner� of one plate

wears the picklehaube of Kaiser Wilhelm II�s army. Pilate, an

over-fed Gruppenf�hrer, crowds the condemned man to the edge of another.

Skeletons wear an

enlisted man�s hat, signifying cannon fodder. �Winter, Leper of the Earth� is

an emblem of dispossession. A heavy-laden figure bends beneath an

indistinguishable burden, left vague to suggest the burdens of living. Pathos

lies in the axis of the pose. Ash

Wednesday brushes every plate.

Several colorful works

quicken the tempo at the end. Swift, animated strokes of translucent oil and

watercolor build poignant expressionist heads, one of Christ, the other a

clown. The final crucifixion, a Good Friday tableau made brilliant with

pigmented aquatint, hints at Easter.

By any measure, this is

an outstanding exhibition that would honor MoMA or the Metropolitan. Biblical themes are indivisible

from our cultural history and need not be relegated to an independent

institution. Yet MOBIA�s

very existence concedes a hidden starting point: that religious motifs,

demythologized by modern methodologies, are a world apart from contemporary

culture. But as Rouault and his circle understood, it is faith that demythologizes

the world.

�Georges

Rouault: Miserere et Guerre� at the Museum of Biblical Art (1865 Broadway at

61st Street, 212-408-1500).

This

review appeared first in The New York Sun, March 30, 2006.

Copyright 2006 Maureen Mullarkey