Secularizing the Sacred

Our Sacred Signs: How Jewish, Christian and Muslim Art Draw from the Same Source by Ori Z. Soltes. Westview Press, $29.95.

By Maureen Mullarkey

OUR SIGNS, THEIR SIGNS, ALL GOD’S CHILL’UN GOT SIGNS. Human history is an alphabet soup of sacred signs. From the caves of Lascaux to the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock, the profanus (you and I) seeks entente with the sacer (you know Who) through visual symbols. The “threefold siblinghood” of Jews, Christians and Muslims dips into the same kettle for their idea of the holy. So why can’t we all just get along?

|

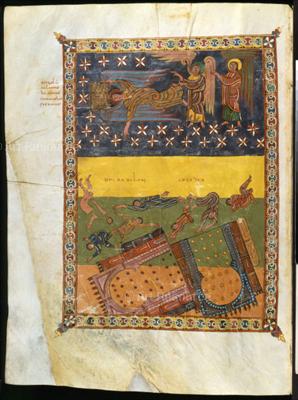

| Warning Angels and the Fall of Babylon (9th century) |

Ori Soltes levels all three “Abrahamic faiths” to a jolly crisscross of symbols adapted to reflect each tradition’s specific “needs.” Use of “needs” is among the earliest of many clues that the author is out of sympathy with religious insight into that which exceeds all representation. He reduces the object of religious intention to an item of cultural history, devoid of transcendent dimension. The book is a riff on Anthropology of Religion for Dummies that wanders from Mesopotamia to Modigliani, Andy Warhol and beyond.

On offer is a lightweight compilation of interesting factlets (e.g. the fearsome nature of Babylonian cherubim; migration of the halo) that do not add up to an argument. Mr. Soltes never touches why, for example, worship of the God of Israel is different from the worship of Baal. Gaps in seriousness are filled with Michelin Green Guide data, engaging yet unrevealing. So, the dome of the Hagia Sophia is flatter than that of Agrippa’s Pantheon in Rome? The information does nothing to illumine the tension between matters of faith and the interpretation of symbols that imperfectly express them. Why bother when it’s all superstitio anyway.

Mr. Soltes’s guidebook pedantry no doubt serves him as a professional lecturer for — among other venues — Archeological Tours and Georgetown University. Not a scholar in any true sense, he collects anecdotes from secondary sources that sound good at tourist destinations or in slide lectures to undergraduates in the art and theology departments at Georgetown. Uneasy with the crucifix, Christianity’s most potent symbol, the university has a fitting multicultural pedagogue in Mr. Soltes.

He indulges the schoolmaster’s habit of repeating Latin words to impress customers. I lost count of the number of times sacer and profanus appear. His prose swims in such phrases as: “interface with sacer and profanus,” “a common profanus perspective,” “the sacer and profanus matrix”. Our lecturer cannot use the words sacred and profane because that would underscore his glaring reliance on Mircea Eliade’s 1957 The Sacred and the Profane a widely influential work by a distinguished historian of religion. Eliade traced manifestations of the sacred from primitive to modern times with scholarship and an empathy for his subject that escapes Mr. Soltes.

Empathy would encumber our tutor, who has a particular icthus to fry. His ambition is to insinuate a banal relativism that rejects the truth claims of all three of the Abrahamic faiths. “It appears that monotheistic faiths require not only belief in one God but an assumption that there is only one proper understanding, and path to, that God.” Such bald reduction of the complexities of given faith traditions and the radical self-understanding that they generate is a typically shallow comparative religion approach. Mr. Soltes makes so bold as to suggest “the possibility that none of us possesses an exclusive conduit to the sacer.” His unspoken distaste for Judeo-Christian insights — irreducible to Islamic variants — assumes that triumphalism is an inevitable corollary to faith.

On moral holiday, our tour guide ignores the theological imperatives that distinguish Judaism and Christianity from their fierce sibling, Islam. One measure of gravity is his refusal to come to terms with Islamic jihad. In his telling, it is a rather benign term, as graceful as Suleiman the Magnifcent’s monogram. Mr. Soltes omits Islam’s prescribed impulse to conquer infidels either by the sword or by migration, which establishes beachheads for the global Ummah. Scrutiny of the externals of religious expression — a sultan’s Koran box, Arabic calligraphy — sidesteps the intrinsic nature of what is expressed.

Mr. Soltes notes that the Gospels are “merely the centerpiece for the larger New Testament.” He flippantly divides the Hebrew Bible and the Gospels into the “Old Thinking and the New Thinking” and refers to Christ as “God Itself.” His simplistic, unnuanced assertion that our Founding Fathers “separated religious conviction from public life” is a transparent pitch for the naked public square. Finally, he comes to his main interest: the place of Jews (as an ethnicity, not a religious group), women and the marginalized Other in Western art. Discussion of a relatively unknown African American artist, Willie Little, is merely an excuse to scold Americans who “exercise prejudice, bigotry and hatred toward those less successful.” In all, the author’s handling of symbols is captive to unacknowledged agendas that ooze out between the lines.

Let this book go straight to the remainder shelf. Readers have more to gain from Louis Dupre’s Symbols of the Sacred or Hans Urs von Balthasar’s essay “Religious Symbols and Aesthetic Form.” Do they know this at Georgetown where the book is meant to be marketed?

This review first appeared in Crisis, April, 2006.

Copyright 2006, Maureen Mullarkey