Material Witnesses

Jane Susan Walp at Tibor de Nagy Gallery; John Morra at Hirschl & Adler Modern

By Maureen Mullarkey

Contemporary culture makes a rumpus over self-expression but neglects discipline and method. Amid the hubbub, two quiet, contemporary painters stand out for the quality of their composure and their patient commitment to developing a steadfast eye: Susan Jane Walp, exhibiting at Tibor de Nagy, and John Morra, opening today at Hirschl Adler. Both excel at representation built on linear probity and formal design principles. Although the character of their realism differs, each raises depiction to an act of witness to the goodness of the material world.

|

| Jane Susan Walp, Grapefruit with Ribbon, 2004 |

Ms. Walp has been painting still lifes with monastic exclusivity for two decades. Over the years, her work has grown richer and more lyrical. On her small canvases, prosaic things — grapefruit halves, a pomegranate, a cardboard container of blueberries — enter into that “anticipatory state of glory” that theologian Hans Küng once said was the ultimate function of the fine arts.

Max Friedländer famously wondered how it happened that “a lemon, a herring and a wine glass can be regarded as objects worth painting in themselves.” He traced the germination of still life, in the Netherlands, to the eventual freedom of painters from an obligation to edify. Yet Ms. Walp, in her art, remains a Florentine for whom the phenomenal world bespeaks a grace that heralds something beyond immediate perception. This is what Stephen Westfall, in the exhibition catalogue, rightly calls “the votive aspect” of her compositions.

"Nasturtiums” (2005) and “Vase with two Zinnias and Xerox” (2004) are appealing homages to Euan Uglow. But her strength resides in more faceted compositions which, though built on a central axis, make nimble use of subordinate asymmetries to invigorate the hieratic stasis. Some imbalances are subtle shifts of color and tone, as in the delicious “Nuts in a Tin Bowl with Two Bricks” (2006); others are concrete and assertive. The contents of “Blueberries with Cork, Knife, Bean and Kale Leaf” provide diagonals to stir the serenity of the central elements.

Ms. Walp’s touch — matte, spare and delicate — is exquisite. That, and reticence before her motifs, links her painting to the example set by Spanish realist Antonio López García. Her words ring true in her work: “Still life asks for a kind of humility and I like that about it — working from a place where the usual demands of the ego are not so helpful and can be temporarily ignored.”

John Morra’s art is more aggressive and wider in range. A former instructor at the Water Street Atelier, he pitches camp among so-called Classical Realists who advance 19th century academic technique as the nonpareil of painting. An ideology of depiction, Classical Realism stuffs an old rabbit back into the hat for the express purpose of pulling it out again.

|

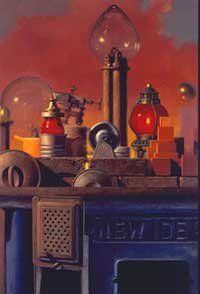

| John Morra, Merz #11 |

That said, Mr. Morra is more than a technician. Though he risks betting the store on facility (rather than on the imaginative qualities served by it), he, like Ms. Walp, seeks amplitude in the ordinary. This is a moral impulse distinct from skills. It is wonderfully present in his Merz series. These are architectonic still lifes of vintage tools and kitchen equipment: 1950’s mixer, juicers, basters, furnace gears, oil cans, egg beaters, bottles — salvage from tag sales, junkyards, and that virtual dump, eBay. With a titular nod to Kurt Schwitters, the paintings confess, not displace, his modernity.

“Merz No. 10” (2006) is a stunt man’s paradise, gleaming with reflections and transparencies within transparencies. (Note that light bulb inside a glass container.) High wire acts thrill us because the performance is hard-won and a slip could be fatal. But there is much more here than circus. Like every work in this splendid series, the composition rises above dazzle and invites interpretation. An enamel Sunbeam mixer, dignified in chiaroscuro, beckons to be understood as something larger than a prop.

Wares are outmoded yet the assemblages are elegiac, not nostalgic. In “Merz No. 11” (2006), industrial oddments, in saturated warm tones, play above the cool blues of a cast iron stove stamped with the logo “New Idea.” It yields a heated metaphor for a manufacturing past which was once a source of national pride and power. A subtle pathos runs through the series like the sound of a muffled drum.

Here, Mr. Morra’s essential subject is his own time reflecting on its own past. It is a kind of double vision that elicits from him an individuating discernment untapped by his landscapes and fruit-and-vegetablescapes. These last are oddly anonymous. They might have been painted by anyone, from Water Street to Beijing, schooled in traditional technique. (Academic painting by skilled young Chinese artists is one more import increasingly visible.) It is Mr. Morra’s opulent configurations of American industrial bric-a-brac that are distinctive and compelling.

The visual world calls each age to revisit it afresh. Because earlier ages have depicted great things — or little things in a great way — does not relieve our own from doing its part. Ms. Walp’s and Mr. Morra’s quotidian solemnities demonstrate why painting still matters.

“Susan Jane Walp: Recent Paintings” at Tibor de Nagy Gallery (724 Fifth Avenue, 212-262-5050).

“John Morra: Recent Paintings” at Hirschl & Adler Modern (21 East 70th Street, 212-535-8810).

This review first appeared in The New York Sun, February 15, 2007.

Copyright 2007, Maureen Mullarkey