Winter Curry II:

Diana Horowitz at Hirschl Adler Modern; Don Beal at Prince

Street Gallery; Gainsborough anyone?

By Maureen Mullarkey

DIANA HOROWITZ' ART is one of

restraint and modulation. The appeal of it lies in her retreat

from self-display in service of her motifs. Behind the work

is a dedication to technical and chromatic means that reveal

the abiding qualities of the subject itself. There are no exhibitionist

flourishes. Only quiet attention to the architecture of city

streets, industrial sites along the New York's commercial waterways,

and the kaleidoscope of Brooklyn rooftops. These are counterposed

to pastoral scenes of the Umbrian countryside.

There is a particular poignancy to this exhibition, Diana Horowitz'

first at Hirschl Adler

Modern. It opened on a night when New Yorkers were hunkered

down, avoiding the subway and looking over their shoulders to

see if the heightened terror alert would end uneventfully or

in atrocity. The subject matter could not have been more timely

in its presentation of two related worlds: one under immediate

threat; the other endangered in ways not yet visible to tourists

who still seek holiday from the race against time in which we

stand reminded that we live.

|

|

| Grain Silo and Still Water,

2002 |

Morning Tibor from Todi, 2001 |

Horowitz' paintings are surprisingly small for the amount of

information they convey and the terrain that individual paintings

cover. She works within the perimeters of the traditional open-air

oil sketch. Fully realized paintings maintain that intimate,

non-imposing scale and sense of immediacy that made the oil

sketch dear to artists themselves from the seventeen to the

nineteenth century. It was a tradition brought to an extraordinary

level of accomplishment by European landscape painters, Corot

among them.

These are Horowitz' antecedents. She makes gracious use of

them, balancing the improvisational appeal of plein air

against the demands of unromantic modern construction. Take

notice of Fifth Street, Gowanus Basin. In a width of

no more than 20 inches, she confronts a wedge of pier that juts

forward, splitting the canal in two. Series of individual pilings

are rendered fluently as a solid block, emphasizing the ingenuity

of the structure as a loading platform and its aggressive pragmatism.

Yellow freight-lifters, too small to be depicted in drab detail,

supply just the right color note to enliven the browns and grays

of the locale.

Light and atmosphere are the heart of the oil sketch. Horowitz

is very good at capturiing daylight, that muting haze from summer

heat or New York smog. Looking at these paintings, I was reminded

of Seurat's comment that he painted landscapes to "wash

the studio light" from his eyes. Her light is faithful

to the effects of sun filtered through atmospheric vapor. In

each of her most satisfying works, a play of grayed tones provides

a stage for the surprise of a deft touch of saturated color.

I love these Brooklyn paintings. I know the settings in real

life. What a delicious shock to be brought up short by suggestions

of undetected beauty in places we hurry to pass. Horowitz' industrial

scenes are not dry reductions to essential forms: those notorious

cylinders, spheres and blocks. Something more humane is at work

here. It as if the unacknowledged splendor of the human labor

performed on these piers were suddenly made visible. That beauty

comes only in flashes, a momentary insight in passing. Hence

the appropriateness of the oil sketch. Horowitz works with an

unprejudiced gaze that greets quotidian neighborhood sights

with as much regard as an Umbrian castle town.

The speed and abridgements of the sketch fail their subject

only in two small paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge seen from

above. Missing is any iindication of the real life majesty of

the bridge. It is rendered, out of necessity, simply as a diagrammatic

pattern across the East River. Or perhaps the impediment is

as much in me as in the paintings. Since the vantage point from

which they were done—a tower studio in the World Trade

Center—is gone forever, I want more from them than a sketch

can bear. I want some sense of the elegiac, the prophetic, a

hint of unease. But of course, that is not fair. When they were

painted it was just one more overcast day in a confident city.

Art is not made in a vacuum. Neither is it viewed in one. No

innocent eyes exist. Just as our understanding of the art of

the past is enhanced by knowledge of the context in which it

was produced, so too, our approach to contemporary art is shaped

by our understanding of the world addressed by it. In all, here

is painting that affirms its own world and earns a welcome from

it.

Hirschl Adler Modern, 21 East 70th Street,

New York 10021 Tel. 212.535.8810

DONALD BEAL'S INSTINCT FOR COLOR

is deeply appealing. And instinct it is. Color sense cannot

be forced. It has to come of itself, rather as memories do,

by natural association and unbidden, long after striving for

it has ceased.

For the majority of contemporary painters, color precedes form.

It is from color that forms are made. Painters committed to

maintaining identifiable reference, however loose, to the world

as it appears, must grant color a structural role. The finest

of Beal's work here maintains a subtle, lyrical balance between

the constructive and expressive uses of color.

|

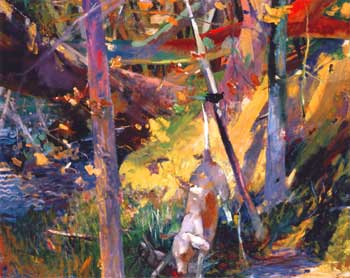

| Woods, Dog and Rabbit, 2002 |

On show—Beal's first at Prince Street—are a series

of large explorations of the Provincetown Beech Forest. Played

fortissimo, they are generous orchestrations of natural scenes

that use color for its lyrical properties without losing touch

with reality. Maura Coughlin's comment in the exhibition brochure

gets it just right in specifying the advantage of the subject

to Beal's coloristic approach:

The Beech Forest landscape is so much less sublime, much

less easy to generalize: it shifts with every footstep and

changes with the seasons. It was without an an obvious horizon,

focal point or delineation between fore, middle and background,

and Beal found it endlessly challenging, demanding its own

complex visual language.

The language is simply that of color, seeded—in the most

convincing works—with hard facts. It is for good reason

that Woods, Dog and Rabbit was chosen for the announcement.

Together with Dogwalker (Red Tree), this is Beal's work

at its most distinctive in terms of color and compositional

discretion. Each of these uses the strong verticals provided

by trees to stabilize the dappled disorder of sunlight and shade

on woodland underbrush. In each, a spotted dog serves as a useful

natural form for providing the needed neutralizing of high-keyed

color rhymes.

Swamp and the over-sized [102' square, hung on the diagonal]

Ladyslippers are lovely to look at. But color sensation

is not the whole of painting. For me—and I make no special

claims for personal taste—these are weakened by having

surrendered too much to abstraction. In each of them, color

spills across the surface, giving the effect of something vague

waiting to be shaped. Pretty, painterly abstractions that abandon

description have become commonplace. The differences between

them, no matter the artist, are more rhetorical than visual.

But Beal has an authentic gift for sustaining tension between

a measured abstraction and visual truth. Why muffle the accomplishment?

The monumental Family Outing is quite different in feel

and in influence. While the landscapes follow the chromatic

lead of earlier colorists, this image of a standing woman seems

more consciously contemporary. David Parks and Richard Diebenkorn

are not far in the distance. It is an impressive painting if

a bit unsettling. Color is more somber here, the rhyming gone.

Its gritty modernity lends it a frisson that the subject

itself might not suggest.

Prince Street Gallery, 530 West 25th Street,

New York NY 10001; Tues - Sat 11 - 6 PM

GAINSBOROUGH, ANYONE? The first

volume of Tate Britain's house magazine features an article

by William Vaughan, "Gainsborough's

Modernity." The title tells us much: we should look

at Gainsborough because he is more up-to-date than we think.

And, yes, that is true. But there is hazard in this approach.

The downside of it is the implication that, were it not for

his crypto-modernity, Gainsborough could be relegated to the

dustbin of history, one dead white curio among a host of others.

In its way, it is a parochial response. It places the burden

of proof on the past. History must convince us moderns of a

reason for engaging with it. We are absolved of any obligation

to enter the past with the same courtesy we would bring with

us to any other foreign country.

Exploration of Gainsborough's relevance to audiences now, rather

than audiences then, is helpful to a point. The past is not

always graspable as something alive that speaks across generations,

let alone centuries. Scholarly efforts to grant it a voice are

welcome. The danger comes in using that past to reinforce the

false metaphor of modernist—and now post-modernist—progress.

Art, like life itself, is not a tale of progress. Some humility,

please! But this is a discussion for another day. In the meantime,

look up Vaughn's article. Better still, try to get hold of a

copy of the splendid, historically informed catalogue

that accompanied the exhibition. It represents art education

at its finest.

Maureen Mullarkey � 2003